Thủ Thuật Hướng dẫn Which of the following definitions of leadership is adapted by your textbook authors? 2022

Dương Minh Dũng đang tìm kiếm từ khóa Which of the following definitions of leadership is adapted by your textbook authors? được Cập Nhật vào lúc : 2022-09-28 23:54:23 . Với phương châm chia sẻ Kinh Nghiệm Hướng dẫn trong nội dung bài viết một cách Chi Tiết 2022. Nếu sau khi Read nội dung bài viết vẫn ko hiểu thì hoàn toàn có thể lại Comment ở cuối bài để Mình lý giải và hướng dẫn lại nha.- Journal List Am J Pharm Educ v.83(9); 2022 Nov PMC6920635

Am J Pharm Educ. 2022 Nov; 83(9): 7520.

Nội dung chính- INTRODUCTIONLeadership Assessments.Recommendations.What is leadership definition by authors?Which of the following is a definition of leadership?What is leadership according to Koontz and O Donnell?What is leadership according to Peter northouse?

Abstract

Objective. To characterize leadership definitions, competencies, and assessment methods used in pharmacy education, based on a systematic review of the literature.

Findings. After undergoing title, abstract, and full-text review, 44 (10%) of 441 articles identified in the initial search were included in this report. Leadership or an aspect of leadership was defined in 37 (84%) articles, and specific leadership competencies were listed or described in 40 (91%) articles. The most common definitions of leadership involved motivating others toward the achievement of a specific goal and leading organizational change. Definitions of leadership in some articles required that individuals hold a formal leadership position whereas others did not. Only two leadership competencies were related to specific areas of knowledge. Most of the competencies identified were interpersonal and self-management skills. In terms of assessment, only one (2.3%) article assessed leadership effectiveness, and none assessed leadership development. Of the remaining 24 (55%) articles that included some type of assessment, most involved behavioral-based tools assessing individual attributes conceptually related to leadership (eg, strengths, emotional intelligence), or self-assessments regarding whether learning objectives in a leadership course had been met.

Summary. Definitions for leadership in pharmacy varied considerably, as did leadership competencies. Most conceptualizations of leadership resembled a combination of established approaches rather than being grounded in a specific theory. If leadership development is to remain a focus within accreditation standards for Doctor of Pharmacy education, a consistent framework for operationalizing it is needed.

Keywords: pharmacy, leadership, affective domain, assessment

INTRODUCTION

Leadership is a highly desired attribute among pharmacists, and some have suggested it should be considered a professional obligation.1 Recognizing its importance among Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) graduates, leadership is listed as a key element in Standard 4 of the 2022 Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards (“Standards 2022”).2 Specifically, Standard 4.2 requires that graduates be “able to demonstrate responsibility for creating and achieving shared goals, regardless of position.” Although examples of co-curricular experiences intended to support Standard 4 are provided in the accompanying ACPE accreditation guidance document, no recommendations exist for how to operationalize leadership development, including how to define, measure, or assess it.3

A cursory review of the literature suggests that definitions of leadership in pharmacy vary considerably, as do expectations regarding the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics to be demonstrated by pharmacy leaders. Additionally, no consensus exists regarding how leadership should be measured and assessed, adding significant ambiguity to how schools of pharmacy should be evaluated on their ability to meet Standard 4.2. In fact, based on some conceptualizations of leadership, such as the trait-based approach (eg, leadership as a reflection of individual traits such as cognitive ability and motivation),4 schools could argue that students with such attributes are sought out during the admissions process and no further efforts to develop leadership are necessary. Expectedly, the extent to which leadership has become integrated into the PharmD curriculum varies. Indeed, many of the reports in the literature have consisted of extracurricular strategies (eg, involvement in professional organizations, medical mission trips) or elective didactic experiences, suggesting that leadership development may still be mostly limited to those students who already demonstrate a proclivity for leadership.5–9

Recent efforts have been made to advance our understanding of leadership in pharmacy via use of the Delphi method.10,11 The Delphi method consists of a series of structured surveys or interviews in which a panel of subject matter experts is guided to consensus by an external mediator. A 26-thành viên Delphi approach was used to identify a set of guiding principles and associated competencies for student leadership development.10,11 Members of the panel were leadership instructors selected on the basis of attending sessions on leadership development American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) meetings, membership in the investigators’ professional network, and the results of a query of the AACP thành viên database. Participants were guided through three rounds of surveys, resulting in the identification of 12 guiding principles and 11 competencies (four related to knowledge, two related to personal leadership commitments, and five related to leadership skills).10,11 A major advantage of the Delphi method is that it encourages dialogue in a confidential and blinded fashion so that the discussion is not dominated by one or more voices.12 However, disadvantages include a lack of standardization (eg, size and composition of the panel, process for selecting panel members) and concerns regarding its validity and reliability.13

The purpose of our research was to complement existing efforts to conceptualize leadership in pharmacy by performing a systematic review of the literature. The primary advantage of this approach is that the totality of scholarship on a topic can be reviewed and evaluated in a systematic way, including perspectives that may be underrepresented in an expert panel. Another advantage is that a systematic review can characterize changes in a construct over time,14 which may be particularly important given the evolution of leadership theories over the last century.15

Using this structured approach, we hoped to accomplish three aims. Our first aim was to compare definitions for pharmacy leadership, including whether they differed from established leadership theories. The second was to characterize the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (ie, competencies) expected of pharmacy leaders, which is essential to the development of instructional strategies. Although use of the term competency in reference to leadership remains controversial in personnel psychology because of the lack of a consensus definition,16 we selected it to be consistent with Standards 2022 and prior research in pharmacy education.10 Finally, we hoped to identify instruments for assessing leadership effectiveness or development, which could be used by schools of pharmacy to evaluate their leadership development efforts. For this latter purpose, we did not differentiate between assessments of leadership effectiveness vs emergence, terms which refer to an individual’s effects on group performance vs his or her ability to rise to the top in an organization, respectively.17

Methods

A literature search was conducted using PubMed and SCOPUS to find English-language articles containing the terms “pharmacy,” “student,” and “leadership.” Two of the authors completed title and abstract reviews, and a third author served as tie-breaker for each round. We determined a priori that agreement of <80% during any phase would prompt clarification of review criteria and the process would be repeated. Interrater agreement for the title and abstract screens was calculated using Cohen’s kappa. All three team members participated in the full-text screen, and exclusion of any additional articles required group consensus.

Articles were included in the title screen if any reference was made to “leadership” and “pharmacy” in the title of the article or the journal in which it was published (eg, an article having been published in the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education would satisfy the “pharmacy” criterion; thus, the title only needed to refer to “leadership” for the article to be included in the study). During the abstract screen, articles were included if they referred to “education” or “training” and least one of the following pertaining to leadership: definitions, competencies, or assessments. Any articles without an abstract were forced into the full-text screen.

During the full-text screen, an article was excluded if it did not provide a definition or conceptualization of leadership, or if upon more detailed analysis, the article did not relate to education or training. The constructs of interest for this study (ie, definitions, competencies, and assessment methods) were also collected during the full-text screen. Given a paucity of methods for assessing leadership effectiveness or development in the full-text screen, data collection was expanded to include any assessments related to leadership, including self-reported leadership perceptions and domains conceptually related to leadership (eg, emotional intelligence).

Following data collection, leadership definitions, competencies, and assessment methods were categorized according to construct similarity based on group consensus (eg, “embracing adversity” and “taking on challenges” were considered similar and thus were grouped together as “perseverance”). Leadership assessment methods were further analyzed to determine whether validated instruments were used.

Results

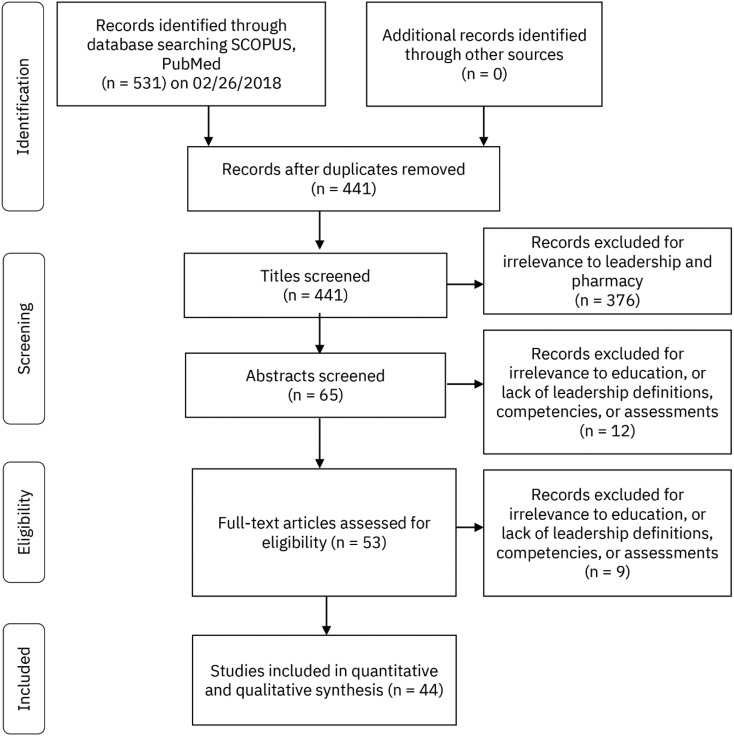

Five hundred thirty-one abstracts were identified in the initial search. Of these, 90 duplicates were removed, leaving 441 abstracts for the title screen. During this phase, the screening authors agreed on 419 of 441 titles (95.0% agreement, κ=0.80, p<.001), and the remaining 22 titles were reconciled by the third author. Three hundred seventy-six articles were deemed irrelevant to the study during the title screen, leaving 65 articles for the abstract screen. Agreement by the screening authors was achieved on 55 of 65 abstracts (84.6% agreement, κ=0.49, p<.001), and after reconciliation by the third author, an additional 12 abstracts were excluded. Of the remaining 53 articles that underwent a full-text screen, nine were excluded based on group consensus, leaving 44 articles for data extraction and analysis. These included 15 descriptions of a leadership course or program, 10 surveys, nine commentaries, three Delphi panels, three qualitative studies, three multimethod studies, and a single literature review. Many of the descriptive studies incorporated surveys (eg, pre- and post-course evaluations), but assessments of leadership perceptions or effectiveness were not their primary focus. A summary of the search strategy using the PRISMA framework is depicted in Figure 1.18

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement Flow Diagram for Search Methods

Eight definitions of leadership were extracted during the analysis (Table 1). The most common definition involved influencing, motivating, enabling, or empowering others, often to achieve a specific goal (11 articles). Two other definitions were commonly cited: the leader as an agent of change (nine articles) and the leader as an individual who receives external recognition for leadership, eg, serving in a formal position, receiving an award (nine articles). Some articles defined leadership in terms of the position held (eg, president),19,20 whereas others indicated that any position was sufficient, including involvement on a committee or task force. Demonstrating leadership without a formal title or position was the fourth most common definition (six articles); “big l” versus “little l” leadership was a common framework used to distinguish between individuals with formal leadership roles and those who lead informally.6,21 Less commonly identified definitions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Terms Used in Published, Peer-Reviewed Articles to Define Leaders or Leadership in Pharmacya

Sixteen leadership competencies were extracted from the literature (Table 2). We classified each competency as an area of knowledge, skill or ability, or other characteristic, based on the framework commonly used in personnel psychology and in accordance with prior leadership research.22,23 Knowledge refers to technical expertise whereas skills and abilities refer to the capacity to perform tasks. Other characteristics include motivations, attitudes, values, interests, and personality traits.23

Table 2.

Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other Characteristics of Pharmacy Leaders Identified Through a Review of Published, Peer-Reviewed Papers

Knowledge of leadership characteristics (including distinctions between leadership and management) and knowledge of the pharmacy profession were the only two areas of technical expertise identified in our analysis. Of the 10 skills and abilities identified, the most common was self-regulation (26 references), or the ability to monitor, reflect upon, and adapt one’s attitudes and behaviors in response to demands (Figure 2). Persuasion, or the ability to influence the thoughts and/or behaviors of others, and strategic planning, an ability to articulate a vision and develop and/or support strategies for accomplishing it, were also common (19 and 17 references, respectively).

Bar Chart Depicting the Frequency of Pharmacy Leadership Competencies as Described in the Literature and Included in This Analysis

Four other characteristics were extracted from the literature. Team and service orientations were mentioned in similar frequencies (nine and eight references, respectively), and a learning orientation was found in four references. An ethical orientation, or the tendency to act in accordance with a set of moral and/or ethical standards, was found in only one reference.

Leadership Assessments.

As described previously, we expanded our criteria to include any instruments related to leadership, including self-reported leadership perceptions and assessments of conceptually related domains. We identified nine such methods, four of which (44%) were validated by prior research (Table 3). The most frequently used method was students’ self-reported achievement of learning objectives for a leadership course or program (nine references). Another common method (six references) was CliftonStrengths (formerly known as StrengthsFinder or StrengthsQuest, Gallup; Washington, DC), a validated instrument for identifying themes of talent upon which leadership and other skills can be built.24 Most references evaluated leadership perceptions rather than competencies. Only one study evaluated leadership effectiveness; however, because of its cross-sectional design, leadership development (ie, a change in effectiveness over time) was not ascertained.25

Table 3.

Methods for Assessing Leadership in Published, Peer-Reviewed Articles

Discussion

Despite a growing emphasis on leadership development in pharmacy, the results of this systematic review indicate that little consensus has been achieved on the definition of leadership in the profession. A similar lack of agreement was observed with regard to leadership competencies, providing little guidance to schools of pharmacy on how leaders should be developed. Not surprisingly, few validated instruments have been identified to measure leadership among pharmacy professionals. The implications of each of these findings and the challenges they pose for operationalizing leadership development in pharmacy education are discussed in further detail below.

The most common conceptualization of leadership revealed in this analysis was an individual who influences or motivates others, often in the achievement of a specific goal. However, this definition was still only used in a quarter of articles, suggesting that considerable disagreement exists. Perhaps the most notable discrepancy in our findings was the use of formal titles or positions to define leadership (seven of the nine references in which leadership was defined by external recognition), and the assertion in others (six articles) that a formal title or position was not necessary for leadership. Given that the remaining definitions of leadership involved performing specific tasks, defining leadership as the attainment of a title or position (or using it as an inclusion criterion for a study) likely restricts the range of competencies that can be captured. Indeed, with perhaps the exception of personnel management, none of the attributes we identified would require that an individual hold a position of leadership, which is consistent with least one aspect of Standard 4.2.

One of our aims was to compare conceptualizations of leadership in pharmacy to established leadership theories. With the exception of definitions that involved medication use and patient care (6.8% of articles analyzed), most resembled a blend of existing leadership frameworks but few were grounded in a specific theory. Many of the conceptualizations most closely resembled transformational leadership, which is characterized by understanding followers’ motivations and empowering them to achieve an aspirational goal.26 Transformational leadership is one of the most popular contemporary approaches to leadership, likely because of its characterization of leadership as a process, its emphasis on leader-follower relationships, and its association with positive work-related outcomes for both individuals (eg, job attitudes) and organizations (eg, performance).15,26,27 We did not find any specific references to the four-factor model of transformational leadership originally articulated by Bass and Avolio (ie, idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration), but other transformational approaches were evident in the reports we reviewed, such as the practices of exemplary leadership proposed by Kouzes and Posner.26,28

Although charisma (often used interchangeably with “idealized influence”) is considered a fundamental feature of transformational leadership, it was not mentioned in any of the articles we analyzed. This finding was consistent with an overall lack of focus on the role that individual traits (eg, personality, cognitive ability) can play in leadership effectiveness, a point we discuss in further detail later in the manuscript. The need for charisma is one of the most commonly cited drawbacks of the transformational approach, as it implies that leadership is less accessible to individuals who lack it.26 Defining leadership according to the transformational approach also presents a challenge to the idea of leadership as a professional obligation, which may also explain the absence of a focus on charisma (among other traits) in the articles we reviewed in this analysis.

Transformational leadership may also be partially reflected in definitions that referred to serving as an agent of change, a term popularized in John Kotter’s book on business leadership, Leading Change.29 Kotter’s eight-step process for leading change borrows from a variety of established leadership and motivational theories, including leader-thành viên exchange (“build the guiding coalition”) and goal theory (“generate short-term wins”). Although Kotter’s change framework was originally applied to business leadership, it has since been used in a variety of organizations, likely because of its greater practicality compared to some of the leadership theories upon which it is based. The latter may also explain the relatively high number of references to change leadership in our analysis.

Other established models of leadership observed in our analysis included servant leadership and authentic leadership. Service was mentioned in only four articles (9.1%), but this may reflect an expectation that all pharmacy professionals, and not just leaders, heed a call to service (as reflected in the Oath of a Pharmacist). Consequently, service may not be an appropriate metric of leadership in pharmacy, especially as quantifying acts of service (eg, number of health fairs attended) may not reflect underlying constructs of interest (eg, altruism). Leading by example was mentioned in two articles and represents an important component of authentic leadership in which leaders connect with their followers through mutual trust.15

As we alluded to previously, an aspect of leadership that was notably absent in our analysis was the role of individual traits and, in particular, personality. Early trait-based approaches to leadership were largely abandoned in favor of situational and contextual models but have gained renewed interest as our taxonomical understanding of personality has improved.15,30 Based on the five-factor model of personality, meta-analytic research has suggested least a moderate correlation between personality and leadership (r=0.48), with extraversion being the trait that best predicts leadership emergence and effectiveness across studies.30 These findings have important implications for the operationalization of leadership development in pharmacy, and they raise questions as to whether leadership should be considered a professional obligation of all graduates. Instead, there may be specific competencies (which are often but not exclusively attributed to leaders) that should serve as targets of development efforts schools of pharmacy.

In terms of the competencies identified in this analysis, only two were specific areas of knowledge: knowledge of leadership characteristics and of the pharmacy profession (eg, history, societal mission). Knowledge of leadership characteristics was also identified as a competency in prior work and was defined as being able to describe the skills, behaviors, and styles of effective leaders.10 However, given the varying and sometimes discrepant conceptualizations of leadership (including those identified in our own analysis), it is unclear how learners should be held accountable for this. An alternative approach could be to encourage students to critically appraise various leadership frameworks and examine the evidence (or lack thereof) connecting certain attributes to leadership effectiveness, and how these are influenced by factors such as culture (eg, Eastern vs Western perspectives) and organizational context. For instructors interested in such a strategy, a set of guiding principles was recently published.31

Although knowledge of the pharmacy profession was also identified as a key area of expertise, little additional detail was typically provided. Indeed, the relationship between an interest in pharmacy history and leadership was the subject of only one cross-sectional survey.32 Conversely, most leadership frameworks place a focus on understanding organizational culture,15 and perhaps leaders in pharmacy must understand both their own organization as well as the profession in which it operates.

Most of the competencies (62.5%) we identified were skills and abilities, which we believe adds considerable value to the literature on leadership in pharmacy. Only a handful of skills have been identified in prior research, and some of these may be challenging to teach and assess in the earlier parts of the pharmacy curriculum.10,11 For example, “collaborate with others” is an important competency to expect of pharmacy graduates, but it requires that learners demonstrate an array of fundamental interpersonal skills, including social insight, relationship-building, and communication. Consequently, we believe that the additional specificity provided in this analysis complements existing work by identifying areas that could serve as targets of further instruction.

In terms of interpersonal skills, social insight was most commonly referred to as emotional intelligence, and several instruments were used to measure this skill.33–35 Although Standards 2022 allude to social and emotional learning (SEL) (eg, self-awareness), the emphasis placed on higher-order constructs such as professionalism, patient advocacy, and cultural sensitivity implies that students are expected to have already developed many foundational SEL skills (eg, self-efficacy, empathy, appreciation for diversity) prior to enrolling in pharmacy school. However, exposure to SEL training varies considerably in primary and secondary educational settings despite evidence that it improves problem-solving and decision-making skills, and increases prosocial behavior.36 Variability in the development of SEL skills may therefore explain why social insight was seen as a distinguishing feature of leaders and may represent a potential target for training.

Relationship-building was often mentioned in the context of professional networking, but an emphasis was placed on both the quantity and quality of relationships, and how the latter helps leaders achieve organizational goals. The fact that strong communication skills were seen as a distinguishing feature of leaders was unsurprising, but these were not restricted to a specific medium. Indeed, leaders were seen as individuals who demonstrated skill in both speaking and written communications.

Two specific types of communication identified in our analysis were persuasion and negotiation, a finding consistent with transformational approaches to leadership. Although the two are conceptually related, negotiation typically involves compromise solutions that may benefit and harm all parties involved. Given the growing emphasis on shared decision-making among the members of interprofessional teams and between teams and patients, negotiating skills may represent an area from which all trainees could benefit. Coursework in communication has been shown to improve negotiating skills and shared decision-making in other health disciplines, and could represent an area of opportunity in pharmacy education.37

In addition to an emphasis on interpersonal relationships, another common theme to emerge from our analysis was self-management, reflected in the competencies of self-regulation, perseverance, and decision-making. In particular, self-regulation skills were alluded to in 26 references (59.1%). Self-awareness is a key element of Standard 4, and reflective learning has been posited as a strategy for promoting personal and professional growth.2,3 Similar to the ambiguity encountered in clinical practice, reflective learning may also help leaders giảm giá with the uncertainties of organizational leadership.38

Reflective learning has also been posited as a strategy for building perseverance (sometimes referred to as resilience or “grit”), which was another competency identified in our analysis. We categorized perseverance as an ability rather than a trait based on research suggesting that it can be developed over time.39 Importantly, most of the research supporting this assertion is derived from children and adolescents, and studies in pharmacy education have failed to show a consistent relationship with academic performance.39 Conversely, these findings could also reflect a ceiling effect caused by the many barriers to professional school that may eliminate individuals with lower levels of perseverance. To our knowledge, no studies have compared the relative level of resilience or grit among student pharmacists to the general population, and studies in other health disciplines have yielded mixed results.40-42 It is therefore unclear whether opportunities exist to further improve this attribute among pharmacy trainees. A more detailed discussion of resiliency and grit among health professional students has been published previously within the Journal.39

Decision-making reflects skills in both critical thinking and judgement, and a clear distinction between these two attributes was not apparent in the literature we analyzed. Formal strategies such as strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analyses may assist students in learning how to identify key considerations when making decisions. Because few decisions facing leaders (or clinicians) are zero-sum, emphasis should also be placed on helping students giảm giá with uncertainty and managing the consequences (both beneficial and adverse) of their decisions. Such strategies would also assist students in developing strategic planning skills, which was also a common theme in our analysis. Although efforts to grow strategic planning skills were usually limited to envisioning exercises, combining these with training in decision-making may help students understand how ideas can be translated into actionable initiatives.

Finally, only one of the competencies in our analysis resembled an attribute mostly associated with positional leadership, which we broadly labeled as personnel management. We used this label to refer to one’s ability to align individuals with the roles for which they are best suited based on an assessment of their attributes (eg, strengths and weaknesses). Although the power to make this type of decision is usually limited to positional leaders, aligning team members with the roles to which they are best suited could also be accomplished by informal leaders. Doing so would require several of the skills mentioned previously (eg, social insight).

The lack of assessments for gauging leadership is one of the most important findings of this research, and it has important implications for schools of pharmacy given the emphasis on leadership in Standards 2022. If students are expected to demonstrate leadership upon graduation and few instruments exist for measuring it, how programs can be held accountable for meeting Standard 4 is unclear.

A lack of leadership instruments may reflect ambiguity in leadership definitions and the competencies that should be expected of pharmacy leaders. Because many of the conceptualizations of leadership in pharmacy already resemble established paradigms and few competencies were unique to pharmacy, time may be better spent adapting existing tools. Similar efforts have been successful with other affective domains, such as the adaptation of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy for use with student pharmacists.43 Conversely, if a pharmacy-centric instrument is desired, a collection of best practices for developing valid and reliable assessments of leadership has been published.44

Importantly, efforts to identify instruments for assessing leadership should clarify whether the intent is to measure leadership emergence or effectiveness. Leadership emergence measures the ability for an individual to rise to the top of an organization but does not necessarily correlate with leadership effectiveness (ie, the leader’s impact on organizational performance). Moreover, although emergence can be shaped by many of the competencies identified in this analysis, it is also subject to influence by organizational politics and reputation management rather than leadership skill.30 Conversely, leadership effectiveness is more challenging to assess, as fewer opportunities exist to measure it given the relatively brief duration of pharmacy school and limited opportunities to serve in a leadership capacity.

We identified a number of gaps and opportunities for future research (Table 4). Several gaps have been discussed in detail above, such as the use of leadership self-perceptions as a surrogate for leader effectiveness and the assessment of individual domains rather than leadership as a whole. The remaining gaps identified in this analysis were methodological in nature. Most of the references we analyzed were descriptions of leadership development programs, but formal analyses of performance were not conducted. Nine studies involved observational or correlational analyses, a methodological limitation common to leadership research in other areas.15,30 For studies that assessed a specific aspect of leadership, many did not use a validated instrument, or authors did not describe the validity of the instrument used. Finally, many references were editorials or commentaries on leadership; we hope the gaps identified in this analysis will serve as an impetus for more original research to answer these important questions.

Table 4.

Gaps Identified in the Literature Regarding Leadership in Pharmacy and Opportunities for Future Research

Recommendations.

As illustrated in this systematic review of the literature, leadership is a complex, multidimensional construct representing a diverse set of underlying competencies that differ considerably based on the approach selected. Because these competencies vary and leadership is least in part determined by personality and other traits (eg, charisma, extraversion), it may not be reasonable or fair to suggest that leadership be a professional obligation of all pharmacists. Furthermore, the dearth of evidence demonstrating that leadership can be developed schools of pharmacy suggests it may also be an unreasonable accreditation standard. Consequently, we recommend that ACPE revisit its use in future versions of the standards. If leadership is to remain an expectation of all pharmacy graduates, additional guidance should be provided regarding the desired framework, as the current description (“creating and achieving shared goals”) only captures a fraction of the competencies identified in this and prior analyses. Based on the current guidance, simply being an effective team thành viên may be a sufficient standard for all graduates to meet.

Several of our recommendations for the Academy relate to leadership research. First, because few of the competencies identified in this analysis seemed specific to pharmacy, future research should be grounded in established leadership theory. Most articles derived leadership definitions and other variables from a variety of models, making it difficult to discern whether improvements in specific skills or behaviors can be theoretically associated with the individual or organizational outcomes observed in prior leadership research. Second, future research should involve the assessment of leadership effectiveness (eg, follower perceptions, impact on organizational performance) and development (ie, changes in effectiveness over time such as before and after an intervention). Third, validated instruments should be used whenever available, or validation research should be performed prior to the use of any newly developed instruments.

A final consideration for the Academy is the role that teams, particularly interprofessional teams, should play in trainees’ conceptualizations of leadership. Leadership is often taught in the context of vertical power dynamics but a growing emphasis on team-based work has contributed to a flattening of organizational structures across industries, and health care is no exception.15 Conversely, despite the assertion by a number of organizations that leadership of the interprofessional health care team should not be limited to physicians,45,46 traditional hierarchies remain the norm many institutions. Consequently, trainees of all health disciplines may be better served by learning about leadership in an interprofessional context rather than the vestigial hierarchies of the past.

The primary methodologic strength of this study is that the authors attempted to extract all relevant literature on leadership in pharmacy rather than approach the research question with a preconceived leadership framework. We believe this permitted us to capture a greater diversity of leadership definitions, competencies, and assessment strategies. Other methodologic strengths included the use of multiple screeners, blinded reviews and ratings each stage of the process, and a high threshold of agreement for study inclusion. Although one of the advantages of a systematic review is to identify changes over time, such a change was not clearly discernible in our research. We attribute this to the fact that 90% of articles were published in the last decade. Several attempts have been made to achieve consensus on leadership and related competencies during this period; thus, an important follow-up to this research would be to determine whether this resulted in coalescence in the literature.

Several limitations warrant further discussion. First, our focus on pharmacy-specific literature was intentional but may have excluded valuable publications in other health professions that could inform the design of instructional strategies in pharmacy education. Second, we did not exclude commentaries, descriptions of leadership courses or programs, or committee reports, which may have led to an overrepresentation of opinions rather than the results of rigorous investigation. We attempted to adjust for this by restricting our analysis to peer-reviewed manuscripts to ensure that commentary was least evaluated by a journal editor and/or independent reviewer. A third limitation was that we grouped items into domains using a grounded theory approach in which text within the analyzed publications served as the basis for each category. All three authors reviewed and reached full agreement on the final themes; however, another set of researchers may have generated slightly different categories. Fourth, we considered an assessment method or instrument to be validated based on whether it had been tested or validated in any population rather than specifically among student pharmacists. This more lenient definition of validity may lead to misclassification bias, as the instruments we considered to be valid may not have been tested in a sample representative of the target population. A final limitation of our research is that we reported the frequency with which each construct was mentioned, ie, the number of publications in which it was found. Having done so may lead readers to the misinterpretation that more frequently mentioned definitions or competences are more important than those receiving less attention in the literature. This is further compounded by the fact that some individuals contributed to multiple publications and, in least one instance, multiple publications originated from the same scholarly effort.10,11 Consequently, we caution the reader against making judgements regarding relative value, as we chose this straightforward, descriptive approach to limit the subjective determinations of the research team.

Conclusion

Despite an emphasis on leadership in Standards 2022, considerable ambiguity exists regarding the conceptualizations of leadership in pharmacy and the competencies that should be expected of pharmacists upon graduation. Furthermore, the lack of instruments for measuring and assessing leadership make it unclear how schools of pharmacy should operationalize leadership development and thus be held accountable for meeting Standard 4.2. Altogether, these findings suggest that leadership, as currently described in Standards 2022, should be critically re-evaluated by ACPE when determining the next set of standards. Fortunately, should leadership remain an area of emphasis in the future, many conceptualizations of the construct in the pharmacy literature resemble established paradigms, suggesting that existing tools and instructional strategies could be adapted for use in pharmacy education. Studies to evaluate these strategies should serve as the subject of future research.

References

1. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on leadership as a professional obligation. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2011;68(23):2293-2295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. February2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pharmd-program-accreditation/. Accessed November 24, 2022.

3. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Guidance for the accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. February2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/GuidanceforStandards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2022.

4. Kirkpatrick SA, Locke EA. Leadership: do traits matter? Exec. 19389779. 1991;5(2):48-60.

5. Bowman BJ, Raney EC. Pilot implementation of a formal leadership development strategy within a student chapter of an American pharmacy organization. Pharm Educ. 2022;16(1):84-87. [Google Scholar]

6. Cole JD, Dell KA. Implementation and effectiveness of a didactic pharmacy leadership elective. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2022;8(5):708-714. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2022.06.010. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Brown D, Brown DL, Yocum CK. Planning a pharmacy-led medical mission trip, part 2: servant leadership and team dynamics. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(6):895-900. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q547. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Fuller PD. Program for developing leadership in pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2012;69(14):1231-1233. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110639. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Hayes M. Effective leadership and advocacy: amplifying professional citizenship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3):1-5. [Google Scholar]

10. Janke KK, Traynor AP, Boyle CJ. Competencies for student leadership development in Doctor of Pharmacy curricula to assist curriculum committees and leadership instructors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 222. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Traynor AP, Boyle CJ, Janke KK. Guiding principles for student leadership development in the doctor of pharmacy program to assist administrators and faculty members in implementing or refining curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 221. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Fletcher AJ, Marchildon GP. Using the Delphi method for qualitative, participatory action research in health leadership. Int J Qual Methods. 2014;13(1):1-18. doi: 10.1177/160940691401300101. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Woudenberg F. An evaluation of Delphi. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 1991;40:131-150. [Google Scholar]

14. Gopalakrishnan S, Ganeshkumar P. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2013;2(1):9-14. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.109934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Northouse PG. Leadership: Theory and Practice. 7th ed. SAGE Publications.

16. Shippmann JS, Ash RA, Batjtsta M, et al.. The practice of competency modeling. Pers Psychol. 2000;53(3):703-740. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2000.tb00220.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Lord RG, de Vader CL, Alliger GM. A meta-analysis of the relation between personality traits and leadership perceptions: An application of validity generalization procedures. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):402-410. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.402. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Bush AA, Buhlinger KM, McLaughlin JE. Identifying shared values for school-affiliated student organizations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;81(9):6076. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6076. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Phillips JA, McLaughlin MM, Gettig JP, Fajiculay JR, Advincula MR. An analysis of motivation factors for students’ pursuit of leadership positions. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(1):Article 8. doi: 10.5688/ajpe79108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Lyons K, Griggs D, Lebovic R, Roth ME, South DA, Hatfield C. The University of North Carolina Medical Center pharmacy resident leadership certificate program. Am J Health-Syst Pharm . 2022;74(6):430-436. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160107. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Ulrich D, Brockbank W, Yeung AK, Lake DC. Human resource competencies: an empirical assessment. Hum Resour Manag. 1995;34(4):473. [Google Scholar]

23. Brannick MT, Levine EL, Morgeson FP. Job and Work Analysis: Methods, Research, and Applications for Human Resource Management . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

24. Hodges TD, Harter JK. A review of the theory and research underlying the strengthsquest program for students. Educ Horiz. 2005;(3):190. [Google Scholar]

25. Ibrahim MIM, Wertheimer AI, Myers MJ, McGhan WF, Knowlton CH. Leadership styles and effectiveness: pharmacists in associations vs. Pharmacists in community settings. J Pharm Mark Manage. 1997;12(1):23-32. doi: 10.3109/J058v12n01_02. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Bass BM, Avolio BJ. Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership. SAGE; 1994. [Google Scholar]

27. Kirkpatrick SA, Locke EA. Direct and indirect effects of three core charismatic leadership components on performance and attitudes. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(1):36-51. [Google Scholar]

28. Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Leadership Challenge. 6th ed. Jossey-Bass; 2022. [Google Scholar]

29. Kotter JP. Leading Change , 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

30. Judge TA, Bono JE, Ilies R, Gerhardt MW. Personality and leadership: a qualitative and quantitative review. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(4):765-780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Collinson D, Tourish D. Teaching leadership critically: new directions for leadership pedagogy. Acad Manag Learn Educ. 2015;14(4):576-594. [Google Scholar]

32. Elmali F, Staiger C, Tekiner H. Can pharmaceutical history courses contribute in building future pharmacy leaders? A preliminary study from Erciyes University, Turkey. Pharm. 2015;70(11):753-754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Haight RC, Kolar C, Nelson MH, Fierke KK, Sucher BJ, Janke KK. Assessing emotionally intelligent leadership in pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;81(2):Article 29. doi: 10.5688/ajpe81229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Hall CM, Enright SM, White SJ, Allen SJ. A quantitative study of the emotional intelligence of participants in the ASHP Foundation’s Pharmacy Leadership Academy. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2015;72(21):1890-1895. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140812. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Nelson MH, Fierke KK, Sucher BJ, Janke KK. Including emotional intelligence in pharmacy curricula to help achieve cape outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(4):Article 48. doi: 10.5688/ajpe79448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Durlak JA, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Weissberg RP, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011;(1):405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Yedidia MJ, Gillespie CC, Kachur E, et al.. Effect of communications training on medical student performance. JAMA. 2003;290(9):1157-1165. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1157. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Tsingos C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Smith L. Reflective practice and its implications for pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(1):18. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Stoffel JM, Cain J. Review of grit and resilience literature within health professions education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;82(2):6150. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Houpy JC, Lee WW, Woodruff JN, Pincavage AT. Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Med Educ Online. 2022;22(1). doi: 10.1080/10872981.2022.1320187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Mehzabin A, Avula K, Mathew E, Joshua A, Shaikh RB, Muttappallymyalil J. Intrinsic component of resilience among entry level medical students in the United Arab Emirates. Aust Med J. 2011;4(10):548-554. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2011.826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Fjortoft N, Van Winkle LJ, Hojat M. Measuring empathy in pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(6):Article 109. doi: 10.5688/ajpe756109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Crawford JA, Kelder J-A. Do we measure leadership effectively? Articulating and evaluating scale development psychometrics for best practice. Leadersh Q.. July 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2022.07.001. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Schottenfeld L, Petersen D, Peikes D, et al.. Creating Patient-Centered Team-Based Primary Care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2022. [Google Scholar]

46. Brush JE, Handberg EM, Biga C, et al.. 2015. ACC Health policy statement on cardiovascular team-based care and the role of advanced practice providers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2118-2136. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.550. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Janke KK, Nelson MH, Bzowyckyj AS, Fuentes DG, Rosenberg E, DiCenzo R. Deliberate integration of student leadership development in Doctor of Pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;80(1):Article 2. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Ross LA, Janke KK, Boyle CJ, et al.. Preparation of faculty members and students to be citizen leaders and pharmacy advocates. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 220. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Traynor AP, Janke KK, Sorensen TD. Using personal strengths with intention in pharmacy: implications for pharmacists, managers, and leaders. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(2):367-376. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M503. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Patterson BJ, Chang EH, Witry MJ, Garza OW, Trewet CB. Pilot evaluation of a continuing professional development tool for developing leadership skills. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9(2):222-229. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.04.006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Sucher B, Nelson M, Brown D. An elective course in leader development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 224. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Janke KK, Traynor AP, Sorensen TD. Student leadership retreat focusing on a commitment to excellence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(3):Article 48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Sorensen TD, Traynor AP, Janke KK. A pharmacy course on leadership and leading change. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(2):Article 23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. White SJ. Will there be a pharmacy leadership crises? an ASHP Foundation Scholar-in-residence report. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62(8):845-855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Lin AY, Altiere RJ, Harris WT, et al.. Leadership: the nexus between challenge and opportunity: reports of the 2002–2003 academic affairs, professional affairs, and research and graduate affairs committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article S05. doi: 10.5688/aj6703S05. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Bailey BJ, Bowers BL, Hammond DA. Peer leadership for pharmacy students. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2022;74(5):282-285. doi: 10.2146/ajhp150944. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Moore RJ, Ginsburg DB. A qualitative study of motivating factors for pharmacy student leadership. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;81(6):114. doi: 10.5688/ajpe816114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Hassali MA, Saleem F, Alrasheedy AA, Ibrahim ZS, Khan TM, Aljadhey H. Leadership attitudes and beliefs of pharmacy students: a cross-sectional study from a Malaysian university. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2022;6(10):189-194. [Google Scholar]

60. Philip A, Desai A, Nguyen PA, et al.. Evaluating pharmacy leader development through the seven action logics. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2022;73(2):82-85. doi: 10.2146/ajhp150162. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Chesnut R, Tran-Johnson J. Impact of a student leadership development program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10): Article 225. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Renzi SE, Sauberan MM, Brazeau DA, Brazeau GA. Relationship between student leadership activities and prepharmacy years in college. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Board C. You don’t need a title to lead. JAPhA. 2022;57(1):7-8. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2022.12.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Kuhn C. Lead from where you stand: roll up your sleeves and lead. JAPhA. 2022;57(1):6-7. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2022.12.001. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Allen GP, Moore WM, Moser LR, Neill KK, Sambamoorthi U, Bell HS. The role of servant leadership and transformational leadership in academic pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;80(7):Article 113. doi: 10.5688/ajpe807113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. White SJ, Wilkin NE, McElroy SR. Leadership development: empowering others to take an active role in patient care. JAPhA. 2012;52(3):308-318. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.12515. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Feller TT, Doucette WR, Witry MJ. Assessing opportunities for student pharmacist leadership development schools of pharmacy in the United States. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;80(5):Article 79. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Haber SL, Buckley K. A leadership journal club for officers of a professional organization for pharmacy students. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2015;7(1):112-116. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2014.09.010. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. Patterson BJ, Garza OW, Witry MJ, Chang EH, Letendre DE, Trewet CB. A leadership elective course developed and taught by graduate students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 223. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Radulovich R. Want to succeed?: EQ is the new IQ. Aust J Pharm. 2022;98(1159):102. [Google Scholar]

71. Wilson JE, Smith MJ, Lambert TL, George DL, Bulkley C. A novel use of photovoice methodology in a leadership APPE and pharmacy leadership elective. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2022;9(6):1042-1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2022.07.018. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. Bloom TJ. Comparison of strengthsquest signature themes in student pharmacists and other health care profession students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;82(1):Article 6142. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

73. Yee GC, Janke KK, Fuller PD, Kelley KA, Scott SA, Sorensen TD. StrengthsFinder signature themes of talent in pharmacy residents four midwestern pharmacy schools. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2022;10(1):61-65. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2022.09.002. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Hsu JC, Girnys JP. National survey regarding the importance of leadership in pgy1 pharmacy practice residency training. Hosp Pharm. 2015;50(11):978-984. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Articles from American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education are provided here courtesy of American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy

What is leadership definition by authors?

According to C.I. Bernard – 'Leadership is the quality of behaviour of the individuals whereby they guide people or their activities in organised efforts'. According to Bernard Keys and Thomas – 'Leadership is the process of influencing and supporting others to work enthusiastically towards achieving objectives'.Which of the following is a definition of leadership?

Leadership is the ability of an individual or a group of individuals to influence and guide followers or other members of an organization.What is leadership according to Koontz and O Donnell?

Harold Koontz, Cyril O'Donnell, and Heinz Weihrich (1986) define leadership as "influence, the art or process of influencing people so that they will strive willingly and enthusiastically toward the achievement of group goals" (p. 397).What is leadership according to Peter northouse?

Peter Northouse (2007) defines leadership as “a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal.” These definitions suggest several components central to the phenomenon of leadership. Tải thêm tài liệu liên quan đến nội dung bài viết Which of the following definitions of leadership is adapted by your textbook authors?