Kinh Nghiệm Hướng dẫn Anna plans to use a powerpoint presentation in her speech. what advice should she follow? Mới Nhất

Hoàng Trung Dũng đang tìm kiếm từ khóa Anna plans to use a powerpoint presentation in her speech. what advice should she follow? được Cập Nhật vào lúc : 2022-10-28 19:22:12 . Với phương châm chia sẻ Thủ Thuật về trong nội dung bài viết một cách Chi Tiết 2022. Nếu sau khi đọc tài liệu vẫn ko hiểu thì hoàn toàn có thể lại Comments ở cuối bài để Mình lý giải và hướng dẫn lại nha.Public speaking is an invaluable skill, but unfortunately it's one that we often don't give enough time or attention to. However, multimedia presentations (like digital stories) can lay the groundwork for developing those skills. Done right, they provide a perfect forum for combining images, text, and powerful oratory in any classroom situation. Not only do they allow students who don't like public speaking to test the waters and build confidence, but they also allow teachers to target instruction to those students who really need support.

Nội dung chính Show- 1. Multimedia presentations develop confidence in language skills.2. Process-driven presentations encourage meaningful feedback.3. Script-writing strengthens ELA skills -- including information literacy.4. Multimedia presentations challenge students to think creatively.5. Choice provides opportunity for students to shine.Tip 1: Know your audienceTip 2: Create a clear, logical structure3. Write for your specific readers: consider shared knowledgeTip 4: Talk in "spoken English" style, not in "written English" styleTip 5: Practice your presentation and practice again!Concluding remarksStay up to dateDo you have a question about academic writing or publishing?What is the most important part of preparing for an oral presentation?What should we use for effective presentation?What should be avoided during most presentation?When developing a multimedia presentation using Powerpoint What is the maximum number of bullets you should generally use per slide?

1. Multimedia presentations develop confidence in language skills.

For students who lack confidence or language skills, a multimedia presentation created using tools such as Adobe Spark, VoiceThread, Google Drive, or iMovie is an opportunity to develop fluency in English (or any target language) without the pressure of speaking live in front of an audience. With the opportunity to record as many times as necessary, the fear of errors can be eliminated, allowing students to focus on content, intonation, and organization.

We can start building the next generation of orators in effective, engaging ways.2. Process-driven presentations encourage meaningful feedback.

With digital presentations, teachers can more easily check in on student progress and offer instructional advice as well. Rather than everything riding on the live speech or presentation, multimedia presentations can be more about process, and with process-driven assignments there is greater opportunity for teachers to conference with students, offer advice, and provide formative feedback. If the presentations are shared via the cloud, that feedback can even come outside of class time.

3. Script-writing strengthens ELA skills -- including information literacy.

All the same planning and organization that goes into writing a good essay goes into creating a good presentation. Students start with a central idea, find supporting ideas and information, structure those to build an argument or explain a concept, and finish with some kind of conclusion. The only element of writing not present in creating a good multimedia presentation is the conventions of writing (punctuation, paragraph structure, and so on), but the framing of ideas and thinking processes are very similar.

Additionally, students have to find appropriate information to support their points of view in a multimedia presentation as well as the photos, audio clips, drawings, or videos that go with them. This requires students to cultivate good information-literacy skills, including searching databases, evaluating resources, and creating citations.

4. Multimedia presentations challenge students to think creatively.

As teachers, if we really want to foster creativity, we can require or encourage students to create their own graphics, images, audio, and video clips. When students must create something, they have to figure out how to represent their ideas -- a form of abstract, symbolic expression that ups the intellectual ante tremendously.

5. Choice provides opportunity for students to shine.

Let's face it: For some of our students, writing essays or reports is a tremendous challenge. That's not to say that it's not a valuable challenge, but in certain situations we're really looking for content, not writing skills. In this case, a multimedia presentation can be the perfect medium for some students to demonstrate a high level of content mastery. Giving students a choice in how they show understanding can be a legitimate way of maintaining high content standards for all students.

With all the digital presentation tools our fingertips, we can start building the next generation of orators in effective, engaging ways. There's no reason not to start today.

The prospect of giving a presentation fills some people with dread, while others relish the experience. However you feel, presenting your work to an audience is a vital part of professional life for researchers and academics. Presentations are a great way to speak directly to people who are interested in your field of study, to gather ideas to push your projects forward, and to make valuable personal connections.

In this article, I'll give some tips to help you prepare an effective presentation and capitalize on the opportunities that giving presentations provides.

Also, you might want to try our e-learning module and quiz on how to change the style of phrases we commonly write in research papers into those we would naturally say aloud in presentations. See Tip 4 below for details.

Tip 1: Know your audience

The first and most important rule of presenting your work is to know your audience members. If you can put yourself in their shoes and understand what they need, you'll be well on your way to a successful presentation. Keep the audience in mind throughout the preparation of your presentation.

By identifying the level of your audience and your shared knowledge, you can provide an appropriate amount of detail when explaining your work. For example, you can decide whether particular technical terms and jargon are appropriate to use and how much explanation is needed for the audience to understand your research.

What is your audience's level of expertise and what knowledge do you have in common?You can also decide how to handle acronyms and abbreviations. For example, NMR, HMQC, and NOESY might be fine to use without definition for a room full of organic chemists, but you might want to explain these terms to other types of chemists or avoid this level of detail altogether for a general audience.

It can be difficult to gauge the right level of detail to provide in your presentation, especially after you have spent years immersed in your specific field of study. If you will be giving a talk to a general audience, try practicing your presentation with a friend or colleague from a different field of study. You might find that something that seems obvious to you needs additional explanation.

Get featured articles and other author resources sent to you in English, Japanese, or both languages via our monthly newsletter.

We will never spam you or sell your information and you can unsubscribe any time | Click to view privacy policy

Tip 2: Create a clear, logical structure

Next, you'll need to think about creating a clear, logical structure that will help your audience understand your work. You're telling a story, so give it a beginning, middle, and end.

To start, it can be helpful to provide a brief overview of your presentation, which will help your audience follow the structure of your presentation. Then, in your introduction, get everyone "on the same page" (i.e., provide them a shared reference point) by giving them a concise background to your work. Don't swamp them with detail, but make sure they have enough information to understand both what your research is about and why it is important (e.g., how it aims to fill a gap in the research or answer a particular problem in the field). By making the foundation of your research clear in the introduction, your audience should be better able to follow the details of your research and your subsequent arguments about its implications.

In the main part of the presentation, talk about your work: what you did, why you did it, and what your main findings were. This is like the Methods and Results sections of a manuscript. Keep a clear focus on what is important and interesting to your audience. Don't fall into the trap of feeling that you have to present every single thing that you did.

Take-home message:

If my audience remembers one thing from my talk, what do I want it to be?

Finally, summarize your main results and discuss their meaning. This is your opportunity to give the audience a strong take-home message and leave a lasting impression. When crafting your take-home message, ask yourself this: If my audience remembers one thing from my talk, what do I want it to be?

When you are considering how long each section should be, it is helpful to remember that the attention of the audience will usually wane after 15–20 minutes, so for longer talks, it's a good idea to keep each segment of your presentation to within this amount of time. Switching to a new section or topic can re-engage people's interest and keep their attention focused.

3. Write for your specific readers: consider shared knowledge

Visual materials, probably in the form of PowerPoint slides, are likely to be a vital part of your presentation. It is crucial to treat the slides as visual support for your audience, rather than as a set of notes for you.

A good slide might have around three clear bullet points on it, written in note form. If you are less confident speaking in English, you can use fuller sentences, but do not write your script out in full on the slide.

As a general rule, avoid reading from your slides; you want the audience to listen to you instead of reading ahead. Also, remember that intonation can be 'flattened' by reading, and you don't want to put the audience to sleep. However, if you need to rely on some written text to explain some difficult points and calm your nerves, make sure you pause and look the audience between these points; then go back to talking and not reading the next slide.

Using clean texts, darker-colored text on lighter-colored backgrounds, and presenting data as figures instead of complete sentences results in easier-to-comprehend slides

Using clean texts, darker-colored text on lighter-colored backgrounds, and presenting data as figures instead of complete sentences results in easier-to-comprehend slides

Ideally, the slides should focus on relevant visual material, such as diagrams, microscope images, or chemical structures. A good diagram can be far easier for people to understand than words alone. Make sure that you point to the slides as you talk. This will help guide the audience's attention to the correct part of the slide, and can keep them engaged with what you are explaining.

Make sure your visual materials are easy to read. Use dark lettering on a pale background for maximum visibility; pale lettering on a dark background can be difficult to read. Choose a standard clear font, like Arial or Times New Roman, and make sure that the size is large enough to be seen from the back of the room. Lay out the slides so that the elements are properly spaced. It is better to split a slide into two or three separate slides instead of overfilling one slide. Although your time is limited, your number of slides is not!

Remember that you are not writing a manuscript, so you don't have to use complete sentences. On your slides, verbs (especially "be" verbs) can be omitted. An example is shown in the figure.

Tip 4: Talk in "spoken English" style, not in "written English" style

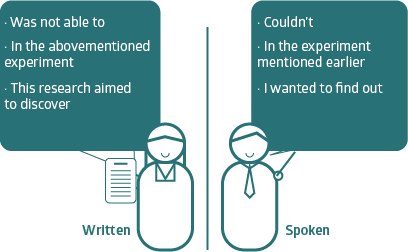

The style of spoken English is quite different from that of written English. If you are preparing your script from text in a research paper, you will need to change the style of the written phrases into that of spoken phrases.

The written English we read in research papers often has a very formal style, using complex vocabulary and grammatical structures. This level of complexity is possible because readers can take their time reading papers to understand the content fully and can look up unfamiliar words or grammatical phrases as needed. This is not possible when listening to spoken English, when the audience hears your point once and fleetingly (this is why brief text and images on your slides can help convey your message fully).

Written English tends to use fewer contractions, more place-centric words such as "above" or "below", and a more formal tone, whereas spoken English uses more contractions, more time-centric words such as "earlier" or "later", and more casual speech.

Written English tends to use fewer contractions, more place-centric words such as "above" or "below", and a more formal tone, whereas spoken English uses more contractions, more time-centric words such as "earlier" or "later", and more casual speech.You can learn about the characteristics of written English versus those of spoken language in a không lấy phí e-learning module and quiz we have prepared.

Also, check back for a later edition of our newsletter to find out how best to deliver your spoken presentation.

Tip 5: Practice your presentation and practice again!

Public speaking is the part of presentations that most people dread. Although it might not be possible to get over your nerves completely, good preparation and practice will give you confidence. Most confident speakers do lots of preparation and use notes well.

After you've written your script, practice and learn is—not so that you learn to say it by rote, but so that it will become easier to remember the important points to say, the links between the points (to maintain the flow of your 'story'), and the words and phrases that express your points clearly.

One way that we ThinkSCIENCE can help you with this is through our audio recording service, in which a native speaker records your script your chosen speed (native speed, slightly slower, or considerably slower). You can then use the recording to practice pronunciation, intonation, and pacing.

Again, if possible, try to avoid reading directly from your slides or script. Once you know your script, you can make a simple set of notes to jog your memory. If you are speaking instead of just reading, you can better engage with your audience and capture their attention.

Leave yourself adequate time to practice your presentation with your notes and slides. Check your timing, remembering that you might speak a little faster if you are nervous, and that you will need to account for changing slides and pointing visual material.

As you rehearse, you will probably notice some words that are awkward to say, particularly if English is not your first language. Check pronunciation with a reliable source, such as www.howjsay.com, an online dictionary, or a native speaker, and then practice to avoid stumbling and putting yourself off during the presentation.

Practice can help you feel more comfortable with your material and more confident to present it to others.

Concluding remarks

Remember the importance of knowing your audience, giving yourself time to prepare thoroughly, and structuring your talk appropriately. And, don't panic!

At ThinkSCIENCE, we have years of experience helping people prepare effective research and conference presentations. From comprehensive editing and translation of your slides and scripts to our audio recording service, we can help you get ready for your presentation. We also offer one-on-one private presentation coaching sessions to help you make the most of your opportunities to present, and provide semester courses to young researchers.

I hope these tips will help you to prepare your English presentations with confidence.

Stay up to date

Our monthly newsletter offers valuable tips on writing and presenting your research most effectively, as well as advice on avoiding or resolving common problems that authors face.

Do you have a question about academic writing or publishing?

Our online Q.&A support service offers researchers, physicians, and academics quick and easy online access to specialist editors.

Ask questions and receive the answers in English or Japanese.

What is the most important part of preparing for an oral presentation?

9. The most important preparation factor is to REHEARSE! You may want to videotape yourself and watch the results with a critical eye. 10.What should we use for effective presentation?

How to prepare an effective presentation. Keep it simple. ... . Create a compelling structure. ... . Use visual aids. ... . Be aware of design techniques and trends. ... . Follow the 10-20-30 rule. ... . Tip #1: Tell stories. ... . Tip #2: Smile and make eye contact with the audience. ... . Tip #3: Work on your stage presence..What should be avoided during most presentation?

Don't try to cram too much information into your slides. Aim for a maximum of three to four words within each bullet point, and no more than three bullets per slide. This doesn't mean that you should spread your content over dozens of slides. Limit yourself to 10 slides or fewer for a 30-minute presentation.When developing a multimedia presentation using Powerpoint What is the maximum number of bullets you should generally use per slide?

Bullets, Fonts, and Text Limit text to 5 or 6 words per line, 3-4 bullets per slide. Use concise wording, and elaborate as you speak. Depending on your content, you may want a different slide for each main point. Tải thêm tài liệu liên quan đến nội dung bài viết Anna plans to use a powerpoint presentation in her speech. what advice should she follow?